Abstract

Reading Dorothy Roberts’s “Killing the Black Body” left me intrigued by the rhetoric used to criminalize women of color, claim control of their bodily autonomy, and deliberately punish mothers with government action. Throughout her book, Roberts gives short examples of real women who’ve been impacted by medical and political decisions guided by this rhetoric. For this project, I expand on those short examples and turn them into a fictional story, while incorporating what I’ve learned from our conversations in this Introduction to Medical Humanities course.

To help me create a thought-provoking and immersing short story, I use Carmen Machado’s “Her Body and Other Parties” as a source of inspiration. Machado’s writing captivates me and leaves me wanting to know more about the broader themes she brings into the narrative, which is my desired effect on readers. I set the story in Mississippi in 1984, a time and place of prevalent sterilization abuse that came to be known as the “Mississippi appendectomy.” Although my story is fictional, the involuntary sterilization of poor Black women in Mississippi happened in real life from the 1920s – 1980s, and unfortunately is one of many.

This short story will focus on a single mother who simultaneously battles an addiction and an attack on her reproductive rights. When pregnant with her third child, evidence of the mother’s addiction resurfaces and a judge forces her to decide between giving up her right to have more children or giving up the right to raise her three children. The mother is faced with a decision that ultimately aims to punish her motherhood more than her drug use. The story will also focus on her doctor, who has seen first-hand the effects of oppressive reproductive laws on the health of her patients and who advocates for the mother during the difficult court case. My goal with this short story is to inspire readers to pay attention to how certain policies disproportionately affect women of color and to urge them to work towards reproductive justice.

Making Motherhood a Crime

The pounding in her head seemed to get louder and she felt nervous. Usually this much noise and movement unfazed her, but the uncertainty was eating at her. Her gaze followed the nurses as they rushed by, avoiding her. Whispering, looking, holding up charts to cover their moving mouths. In an attempt to ignore them, she laid back against the pillow and looked up. Now the lights bothered her. Why were they so bright? She thought her eyes would melt from the intensity of those repeating rectangles in the ceiling. Trying to get comfortable, she closed her tired eyes and wiggled the toes on her swollen feet. Now the incessant ringing of the phones in the reception desk and the never-ending typing on chunky keyboards bothered her. Such a dreadful sound that interrupted the deepest of thoughts. At that moment, she didn’t feel like herself, and she knew it was because she was about to hear bad news. Despite knowing what was coming, a small part of her hoped that she would be able to escape her fate with the kind of luck she’d never had in her life before. Suddenly, she heard the familiar soft clicking of heels approaching and sat up as fast as she could, one hand on her giant belly. Sure enough, there was Dr. Afiya standing before her. Upon looking at the doctor’s face, she knew luck would never be on her side and felt her heart clench. The doctor sighed. “We have your toxicology report. Traces of cocaine were found in your system. I’m afraid I’ll have to call them, as we discussed before,” said Dr. Afiya. She covered her face with her hands and took in the news. In all her 28 years of living in Clarksdale, Mississippi, she never before had wanted to run far away as much as she did that day. Dr. Afiya put her arm on her shoulder and said, “I know you’ve been trying. Hard. I’ll let them know you’ve been working on this and see what I can do for you. You should call home and let them know you will not be able to return today.” As the soft click of heels faded into the distance, she thought about what she would tell her kids on the phone. Could she turn this into another story to entertain them enough to be patient?

Her daughter and son, like herself, were fond of stories. Good stories. The kind of stories that let the imagination run wild and let one escape the world for a moment. Stories that reminded them that life was bigger than the problems of everyday living. Stories whose ending felt like a cold shower of reality, and like gravity was pulling down slightly harder than before. She had grown up with a family of storytellers, and her fondest childhood memories were those of her sitting down for story-time in elementary school. While her teacher held the book open facing the class, she could stare at the book cover and enter a different realm in her mind. Nowadays, she came up with stories to distract herself and her children from the difficulties of raising a family as a single mother with very little income. Poverty was not new to her, which is why she did everything she could to provide her kids with a more stable life. Growing up, she found herself hanging out with a vulnerable crowd, which led to an addiction that seeped into every corner of her life. For years she had been trying to release herself from the tight grip of a substance, a grip that seemed concrete and in place. She had managed to stop for the duration of her last two pregnancies, and she even started to believe that she was finally finding some peace. Then the grip tightened, leaving her weak to her body’s impulses and whatever chemical reactions wouldn’t let her move on. Fighting what seemed like an uphill battle was exhausting, but the happiness her children brought her helped her cope. Her mother had always told her that children were the greatest blessings one could have, and she believed that. Now she had to figure out how to tell her kids that she wouldn’t be home to tell them a bedtime story this time, and who knew when or if she’d return. Her hands on her face provided a comforting darkness to contrast the bright room, and now the silence numbed her ears to everything except her pounding heart.

“I see. But you must understand, she has been trying different rehabilitation centers for a while now. I think it’s in her and the baby’s best interest for her to enter rehab, instead of separating them. I know what the policy is, but I’m looking out for my two patients. How soon can her public defender get here? Alright, I’ll be in contact again soon. Good-bye.” Dr. Afiya put the phone down. Unbelievable. She had made calls like this before, but it never got easier. And it shouldn’t. She looked at the toxicology report on her desk, fixating her eyes on her signature at the bottom left. With a stroke of a pen, she had just made her patients’ life harder. It felt like every time she made a call about a report like that, she had to remind the person on the other end of the line that they were talking about a living, breathing person. Two, really. Next to the toxicology report was a framed picture of her niece. Dr. Afiya didn’t have children of her own, but she loved her niece like a daughter. She found joy in her work and had pushed the thought of having children aside, focusing on helping other women bring healthy children into the world safely, instead. She thought back to a case that had changed her life and the way she practiced medicine forever. During her first years working at a maternity clinic, a patient in critical condition was rushed in. The patient was a young woman, barely conscious, with severe cervical scarring and bleeding. That day, a younger Dr. Afiya lost the patient, who unfortunately didn’t survive a botched abortion. After that tragedy, Dr. Afiya looked into organizations working to make safe abortions accessible to women and to inform them of the options available to them. She kept up to date with news related to the reproductive justice movement on TV and the newspaper, trying to get informed in between rounds and the many things demanding her attention. Every day, she would come home after a long day of work and find herself thinking about her patients, wondering whether or not she helped them as best she could. Today, she wondered if that phone call was going to separate a child and a mother, or give them both a better chance at a healthy life.

It didn’t give them both a chance. Days after that call, the mother appeared in court to face the charges against her. The judge looked at her through his thick lenses, his tiny beady eyes focused on her. Thin veins popped out of his wrinkled hand as he adjusted the mallet in place. At that very moment, he was looking back at her. Specifically, he was focused on the discolored track marks exposing her injection sites. Some were old scars, some were purple bruises that she could hide if she turned her arm at the right angle. The mother wondered if he could see through her, if he could figure out that mentally, she was imagining herself anywhere but there. After the toxicology report had shown traces of cocaine in her system, the mother was arrested. In her mind, she was now coming up with new stories to tell her other two children when she saw them again, while gently rubbing her stomach.

Once upon a time….”Charged with child abuse and child neglect!”….not long ago….”distributing drugs to a minor!”….in a distant land….”endangering life of the unborn child!”….lived a happy family of four….”8 year sentence!”….in a whimsical cottage surrounded by forest….”crack baby will require expensive medical care!”….where the trees sung with the bees….”no maternal instinct!”….and the children roamed free…

The judge recited his story. Loudly. Aggressively. The sight of the mallet interrupted her thoughts, and she couldn’t concentrate or finish her story. Her head started pounding, and she imagined the mallet pounding to the same beat. He was holding on to it with such force, she could imagine it snapping in half. The judge already had his story completed in his mind, and he had chosen the ending. It was decided that she was an unfit mother, and that her pleas to be put into a rehabilitation center instead of jail fell to deaf ears and tiny beady eyes. She tuned out the noise in the room and looked around. Her public defender was speaking to the judge; they were going back and forth.

“Your Honor, she is committed to joining a rehabilitation center to fight her addiction. Her doctor agrees that this is best for her and the child.”

“She made the conscious decision to consume an addictive substance during pregnancy. What kind of good mother does that? It seems to me like she cares more about her quick high than the child.”

“She has no criminal record and has two other children at home that need her. It is also in their best interest that she is given a chance to recuperate and not sent to jail. This is a drug use crime, she should be given the option to enter rehabilitation”

“I’m willing to put her on probation and have her submit to regular drug testing until the child is born. Should she accept this alternative, she must use the contraceptive Norplant after the child is born and until she is no longer an addict. She’s already on welfare, and crack babies use up enough of our taxpayer money.”

“Your Honor, Norplant was approved by the FDA less than a month ago. We’ll need to consult with her doctor to see if it is a safe option.”

“Absolutely not. Her high blood pressure puts her at risk. It would be medically irresponsible for me to administer Norplant, given the complications it could cause her,” said Dr. Afiya. The mother and the public defender were in the doctor’s office discussing the alternative. “I’ve informed the judge that the producers themselves warn against usage by people with her condition. He refuses to provide a different choice and urges her to consent to being on birth control until her addiction is under control,” said the public defender. “Why is he so set on Norplant?” asked the doctor. The defender sighed and replied, “He argued that it’s more convenient. He believes that because it is reversible she shouldn’t have any complications. According to him, it’s easy to just take it off. Like contact lenses or something.” Dr. Afiya laid back in her chair in disbelief, closing her eyes as she rolled them. Her patient’s fate was being determined by someone who failed to inform himself about the complications and dangers of what he believed was the perfect solution. She thought back to earlier that morning, when her daily scroll through New York Times led her to an article about crack babies being “born addicted.” Appalled, she had taken it upon herself to email the writer with attached research publications that contradicted the entire article. She looked over to her desk, smelling the cup full of mint tea that had gotten cold waiting for her. She had recently decided to stop drinking coffee, after getting unbearable headaches on days without caffeine. It was obviously a caffeine addiction. “When will I be able to go home to my kids?” The mother’s question broke through the silence.

This all reminded the mother of a story she had once told her daughter.

There was a firebird that woke up with a gasp for air. Quickly and frantically, it flew all over the place, searching for something. Burning leaves to a crisp, leaving an ash trail wherever it went. It couldn’t find it, and time was running out. The sun was about to set. The firebird searched and searched, never setting foot on the ground. It looked, it listened, and it burned. Something bright glistened in the sun, and it caught the firebird’s eye. The firebird closed its wings and dove fast towards the moving brightness. Within seconds, it was met with warm, salty water that became heavier and heavier. It had been but a reflection of sunlight bouncing on the ocean water, luring the firebird into the peaceful depths. No luck.

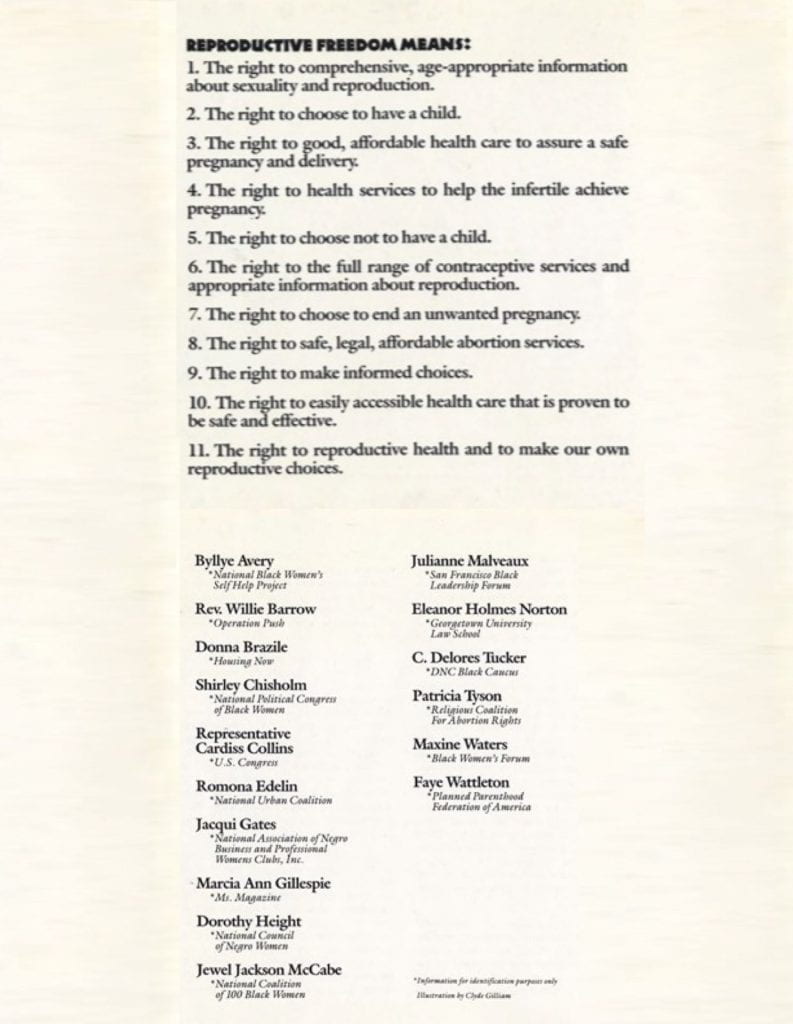

Weeks later, Dr. Afiya found herself surrounded by powerful women in a roundtable. The sound of busy heels thudding against the carpet, the smell of expensive perfumes, and the clicking of pens brought her back to reality. This was where she needed to be. On the way to the meeting, she had driven past protesters. Women holding up signs: NORPLANT KILLS BABIES. Anger in their fierce blue eyes, dripping from their shouting mouths. And what about the mothers? She turned up the radio to tune out the protesting just when the Reagan vs. Mondale presidential debate was announced. Now she was sitting next to women who were signing documents left and right, passing them around the table. She was here, among these women, because the mother had accepted Norplant, despite the doctor’s objection due to the increased health risks. Her objection was valid, but it carried guilt. How could she ask the mother to spend eight years in a cell, away from her 3 children, one of them born only three weeks ago? Now that the baby was born, the mother would have to get Norplant once she became stable after an arduous labor. The state had decided that she was to give up her choice to have children, or else be locked away in a cell. In the end, she was punished for having a baby, not an addiction. The mother decided to take this punishment, if it meant being home with her blessings and being there for them. As she had told Dr. Afiya, telling them stories in person was better than telling them through a phone call that charged by the minute. The doctor averted her eyes down at her phone screen, the wallpaper a picture of her and her niece riding bicycles. With one swift motion, the pamphlet was passed down to Dr. Afiya, and she looked at the second item on the list. With a stroke of her pen, she signed the pamphlet.

William, Clyde. We Remember pamphlet. 1989. Women of Color Partnership of the Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice

References

- Black Feminisms. “The Sterilization of Black Women & the Black Feminist Movement Against Eugenics.” Blackfeminisms, 2017, www.blackfeminisms.com/sterilization/. Accessed 15 Oct. 2020.

- If When How Lawyering for Reproductive Justice. Women of Color and the Struggle for Reproductive Justice. If/When/How, 2016, vawnet.org/sites/default/files/materials/files/2016-08/Women-of-Color-and-the-Struggle-for-RJ-Issue-Brief.pdf.

- Machado, Carmen. “The Husband Stitch.” Her Body and Other Parties, Graywolf Press, 2017, pp. 3-31.

- Roberts, Dorothy. Killing the Black Body. Vintage Books, 1997.

- Whaley, Natelegé. “Black women and the fight for abortion rights: How this brochure sparked the movement for reproductive freedom.” NBC News, 25 March 2019, www.nbcnews.com/news/nbcblk/black-women-fight-abortion-rights-how-brochure-sparked-movement-reproductive-n983216. Accessed 15 Oct. 2020.

- William, Clyde. We Remember pamphlet. 1989. Women of Color Partnership of the Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice