Abstract

The practice of medicine is fundamentally broken down into the physician’s responsibility to place the patient’s welfare above any self-interest or other obligation and to advocate for that welfare. In most cases, this relationship is usually mutual as there is a common goal. This piece consists of 4 separate but connecting op-eds focused on the overarching relationship between the physician and the patient. Each op-ed, however, has a specific subtopic that it discusses. Starting off, I discuss my own personal experience with a physician leading to my inspiration for this piece. I talk about the broader physician-patient relationship and the implications that this relationship has on treatment outcomes. My next op-ed delves into the power dynamic this specific relationship has. Given the level of respect and authority a doctor is given in our society, you would expect them to have all the power in the relationship, but I explore how patients can misuse the power that they hold as well. The third op-ed focuses on a specific case in which the physician-patient relationship is strained and a code of ethics is called into question. I essentially look at the question: what happens when a patient demands a treatment that contradicts medical practicality? I delve into the disagreements a patient and their family can have with their doctor and the different possible outcomes that can result from that. The final op-ed in this piece is a focus on how patients can balance the scales while not becoming a bystander in their treatment. I specifically talk about the shared decision-making model and how treatment outcomes are positively affected when patients are at the forefront of their own treatment. My sources were chosen based on similarity in style or if they had content where a patient went through an experience relevant to the broader discussion at hand. My research content was garnered from other research papers and online sources.

Are Doctors Really The Good Guys?

It was my third time biking to the O’Quinn Medical Tower in the Texas Medical Center. I parked my bike exactly where I had the last two times and found my way to the elevator. One button click and one minute later, I found myself in your standard medical waiting room. Colorful posters plastered the walls, a shelf full of healthy snacks stood in the corner, and my arms were near shivering as the room was extra cold. Probably the most pertinent thing in the room was the ‘Neurology’ label on the door I saw when I walked in, indicative of the reason for my visit. I had been getting migraines for the past couple of weeks, and given the fact that they were interfering with my school work, my parents decided it would be best to get a neurology consult considering I already had a history with the ailment. This third visit was a check-up as I had seen this specialist two times prior.

I remember sitting in the waiting room more worried about the test I had later that evening than the checkup I was about to have. I also had forgotten to eat as it was early in the morning and I had rushed to bike there. I quickly grabbed one of the granola bars sitting on the shelf as I filled out some insurance papers. Soon enough, my name was called and I followed a nurse into a back room where she began to take my vitals.

Temperature. Weight. Height. “Check”

Blood pressure. “Your standing BP is lower than your sitting BP which means you’re dehydrated so drink some water”. I made a mental note to fill my water bottle more often.

I finally got to the actual doctor’s office, which was unlike any typical family physician’s office. There was no patient exam table and I instead sat on a really comfortable couch. It was somehow almost too plush. Directly in front of me sat the neurologist alongside an intern who was taking notes.

“Why haven’t you gotten your medicine from the pharmacy”. Her first statement to me took me by surprise as I was not even aware of any medication. I told her as such but she didn’t believe me.

“I have many problem children like you who refuse to take the medication I prescribe. Why even come to me then?” Not only was I confused, but the use of the phrase “problem child” seemed completely unnecessary. The previous 2 visits had been so pleasant and I didn’t understand where this outburst was coming from. I could see the intern also starting to feel a little uncomfortable.

Instead of expressing my irritation and addressing her unprofessionalism, I found myself silently seething but outwardly accepting her criticisms and blame. In the moment, it was a doctor against a patient and who was I to say anything. I left that doctor’s appointment regretting my lack of assertiveness and I realized how important doctor-patient communication is in the successful treatment of the patient. Needless to say, I ended up finding a different doctor and different place to park my bike for the fourth visit.

A patient-physician relationship is founded when a physician serves a patient’s medical needs; this relationship is also strongly founded on trust. The physician has a moral responsibility to place the patients’ treatment above their own self-interests. The patient expects the physician to give them sound medical judgment and to advocate for their welfare. Patients’ trust in their physicians has in fact been demonstrated to be more important than treatment satisfaction in predictions of overall satisfaction with care (Pearson, 2000).

Studies have also shown that trust is additionally a strong predictor of a patient continuing with their provider (Pearson, 2000). Trust extends to many aspects of the physician-patient relationship. Patient’s level of trust correlates to how they assess a physicians’ willingness to listen to them, whether they feel comfortable enough to actually engage in dialogue related to their health concerns, and whether the physician will value their ability to make informed decisions. In my case, I had relatively zero trust in my clinician after my visit as she had no interest in listening to me. Lack of trust destroys the relationship.

What could’ve been the easy solution in my case was effective communication. If I had just expressed my opinions, then the relationship might have been maintained. Effective communication between physicians and patients can result in positive outcomes through increased patient satisfaction. Effective communication can also influence outcomes such as mental health, pain control, and physiological measures. On the other hand, miscommunication can cause negative implications such as hindering patient understanding, decreasing overall patient satisfaction, lowering expectations of treatment, and reducing patient hopefulness (Johnson, 2019).

Health care these days is focusing around the patient-centered model, which encourages collaboration among patients and physicians to create shared health goals in addressing identified problems. By letting the patient get a greater understanding of the health problems and treatments available, they are also more likely to adhere to treatment plans in the long run. Health care providers are looking for ways to adopt more personalized approaches to health care and targeting factors that affect the physician-patient relationship is one key way to accomplish this.

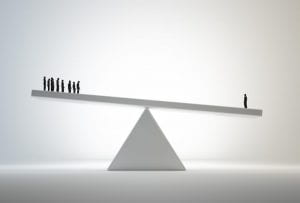

Doctors and their Patients: The Seesaw of Power

Dr. Sandeep Jaudhar had been treating a 22-year old male for severe heart failure. Knowing his chances of survival were slim and seeing him in a state of pain, his family told the doctor to withhold the information from him. Dr. Jaudhar was put in a tough place: should he do his professional duty and inform the patient or misuse his power and respect the wishes of the family? What would you do?

The relationship between a patient and a physician is seemingly sacred. It thus begs the question as to what reasons could come for either party to misuse their power and alter the dynamic.

Misuse of power tends to fall into the realms of monetary gain, social authority, or intellectual advantage (source). Doctors, for example, may recommend unnecessary treatments or follow-up consultations so that they can increase the fees they charge. In addition, they may charge excessive fees where patients cannot access alternative services. When you go to the hospital, you never really ask questions about your care because you just assume the doctors have your best interest at heart. Yet, to be honest there is actually a conflict of interest. In certain cases, the doctor may intentionally not streamline care so the patient can stay in the hospital longer.

This misuse of power extends to the realm of knowledge and professionalism when physicians may intentionally delay referrals to other doctors when they know their own skill is lacking. Their own ego is getting in the way of the patient’s care. Doctors of this breed accept minimum standards rather than continually aiming for distinction in their field. They do this by intentionally performing poorly one year so that their goals for the next year are set lower for them. This is the classic lowering of expectations you see from underperforming students, but it’s not something you want to see from your medical professional. Quite possibly the worst form of power abuse is the decision to withhold medical information from the patient just to maintain a position of superiority. The patient more than likely did not go to medical school and is paying the physician for the sole purpose of conveying medical information to her. Punishing the patient in this manner is a direct hindrance to the treatment of that patient and a blatant disregard for the Hippocratic oath sworn upon by the physician.

The last realm of abuse for physicians and likely the most heinous is that of social authority. In this viewpoint, doctors take it upon themselves to ‘play God’. They may selectively choose cases of either abortion or euthanasia, both instances in which it is their decision to essentially end a life. Some physicians may see it as their way of enhancing the human race in their own twisted form of eugenics. Nonetheless, a physician’s own moral standings should never get in the way of a purely medical decision regarding the patient.

You wouldn’t expect patients to have any power to abuse in this relationship, but in actuality, there are plenty of scenarios in which they do so. In terms of monetary gain, patients may be dishonest by bringing forth lawsuits against their doctors claiming malpractice when the doctors actually did nothing wrong. What the patient isn’t realizing is that they’re not just taking money from the hospital and the doctor, they’re also taking away time the doctor could spend treating other patients while that doctor is tied up in court. Worst of all is the tarnishing of the reputation of the individual which is worth much more in their field.

Another way to abuse power is in a simpler fashion and something that you might’ve done. Think of the last time you went in for a checkup and the doctor asked about your smoking and drinking habits or something personal like that. Did you tell the truth? Giving false information is a form of misuse; doctors withholding information to patients is considered disgraceful so why aren’t patients held to the same standard? Not to mention patients may blatantly lie about symptoms to receive prescriptions for restricted drugs.

There is a specific subset of patients known as ‘heartsink’ patients who don’t actually want to get well but just want confirmation that they are special. In the medical model, a patient’s role is to do their best to get better in response to a doctor’s treatment. ‘Heartsink’ patients don’t adhere to this relationship. They intentionally sabotage the doctor’s attempts at helping them and will manipulate them into making wrong decisions against their better judgment (Laidlaw and Goodyear-Smith,1997). They don’t want anyone to find out what is wrong with them so that they can be special forever. Nonetheless, this interference with treatment is still a misuse of power.

Both physicians and patients have power and the ability to misuse that power for their own gain. So what did Dr. Jaudhar end up doing? He actually did withhold the information… at least initially. Over a few days, he still ended up telling the patient all the necessary medical information when he was in a more composed state. On paper, it may seem like a misuse of power, but a judgment call such as this one actually ends up having an overall positive effect. So where do we draw the line? We honestly don’t know and we hope we can rely on more physicians like Dr. Jaudhar to make the right decisions when it comes to these decisions.

Argue With Your Doctor: Yes?

Alexandra Godfrey, pregnant and knowing she was about to lose the baby midterm, stood in the ER with a decision to make. Her ER doctor repeated the same thing to her, “‘High blood pressure might damage your kidneys or your heart’” (Godfrey, 2017). Yet, Alexandra didn’t care about herself. She wanted to leave against medical advice (AMA) because she wanted to spend the remaining days with her unborn child alone, not hooked up and sedated. Yet the ER physician, going by the books simply couldn’t understand that decision. What we had come to was a patient demanding a decision that went against medical practicality; in Alexandra’s eyes, it was the right thing to do. She even told the doctor, “‘look up the word empathy’” (Godfrey, 2017) emphasizing her defiance.

Doctors and patients can come to disagreements about treatment even if the doctor has the patient’s best wishes in mind. Whereas the doctor may form a course of action from a strictly medical point of view, the patient may prioritize other factors such as spending time outside the hospital or finding personal meaning in the condition through outlets such as story-telling. “Disagreement appears likely to occur when patients’ choices seem misguided to doctors, patients believe their stories have not been heard, or the doctor is unwilling to accept the right of patients to make informed decisions for themselves” (Goodyear-Smith, 2001).

Nowadays medical information is more readily accessible on the internet so patients will take information out of context and even request inappropriate diagnostic tests. Having a slight pain in your lower back doesn’t necessarily justify an MRI scan. Some common reasons for disagreements on a course of action include hearing about a medication’s side effects, not wanting to endure the full length of treatment (take chemotherapy), simply disagreeing with the treatment plan, worrying about complications, or thinking an alternative plan would be safer or more effective. More problems can arise if the patient continually negotiates with the physician, leading them to believe that they’re questioning their authority or ability to help them.

It’s important, however, for physicians to at least address these concerns. A lot of physicians may lack the time or motivation to listen to patients, which is what frustrates the patients and their families. The patients understand that there are certain constraints under which doctors operate, but doctors should also realize that patients have just as much a right to explore every option with the expectation that their doctors will actively listen to their opinions.

There are different outcomes that can result from this disagreement. Given that the consultation will lead to a management plan with both short and long-term outcomes, an agreement can be reached on one, both, or neither of those outcomes by the parties. What actually tends to happen is that a patient might not accept the ideal treatment option for their situation but they will instead gain valuable knowledge about how to prevent or manage a recurrence. In this way, disagreement can actually lead to positive outcomes.

Be Aware of Your Care

Elizabeth Rankin was a heart patient in need of a stent, which is a common medical procedure. Specifically, Elizabeth was recommended to get a drug-eluting stent. Physicians have a bias towards using drug-eluting stents that are coated with medication because they help prevent the growth of scar tissue in the artery lining, ensuring good blood flow. The problem in Elizabeth’s case, however, is that she realized that she was unable to tolerate the eluted drug Clopidrogrel as she developed bruised over her body when she took it. A drug-eluting stent would actually be detrimental to her health in her eyes, which is why she preferred a bare-metal stent. Had the doctor consulted with Elizabeth in regards to her opinions about the treatment plan, the risk of detrimental treatment would have been reduced significantly.

Physicians have to understand and respect the value of the shared decision-making process. By having a vested interest in protecting a patient’s right to making decisions they feel are right for themselves, a treatment plan is created in which all parties are happy. This is also one of the more effective strategies in balancing the scales when it comes to the physician-patient relationship as communication is clear in this model.

When forming the proper treatment for a patient, physicians should take the needs of their patients into consideration. Physicians and patients bring different but just as important ideas to the decision-making process. What the doctor brings to the table is knowledge of the disease, a likely prognosis, as well as tests and the resources for treatment. Sometimes when a medical decision is to be made, there is one clear treatment path. However, for decisions in which there is more than one option, the patient’s own priorities are important to reach a treatment decision. Only patients can truly foresee how a disease will impact their daily life, so they may value a treatment option different than the physician’s because it fits their lifestyle better than the other. The shared decision-making model recognizes the patient’s right to make these decisions, given that they are fully informed about the options they face while allowing providers to feel confident in the care they prescribe.

When conflict arises, the ideal solution is to share power. Power and moral authority should not be exclusively held by the physician but should be a process of decision-making based on mutual participation and respect. To clarify role ambiguities, resolve differences of interest, and reach shared decisions, doctors have certain steps they should take. Firstmost, they should encourage patients to articulate their understanding of their condition and see what possible treatments they have in mind. They should then inform patients about the medical facts about their condition, give them the treatment and support options available, and layout the risks and benefits of each option. Finally, a decision should be made in which there is a mutual understanding of all the information and both parties will be understanding of the outcome, negative or positive. Patient-centered care relies on the active engagement of patients in decisions about their care, so these steps are crucial.

Shared decision-making is the prime method of balancing the scales in the physician-patient relationship. Effective communication where the opinions of both parties are respected not only leads to reduced power dynamics but also to better treatment outcomes. “Patients who feel in control of their own lives and who are actively involved in decision-making about their healthcare have significantly improved health outcomes” (Goodyear-Smith, 2001). There are also other factors for the patient to consider when trying to gain power in the physician-patient relationship. They have to realize that respect doesn’t equate to subservience. Physicians definitely garner our respect, but that doesn’t mean we have to put them on a pedestal. The option to seek a second opinion is always available. Additionally, knowledge is power, and given how readily accessible knowledge is with the internet, knowledge can be in the hands of the patients. Physicians have years of medical knowledge to back their diagnoses, but only a patient can know their own body, and that in in of itself is enough to push back if you know something isn’t working. Technology is much more advanced and accessible now, so not only can physicians communicate more effectively but patients can also do their own research.

The goal is to be like Elizabeth: be an active participant in your treatment. Not only will this create a level playing field in terms of power with your physician, but you’re the one who’s gonna be going through the treatment at the end of the day so might as well have a say in it.

References

Godfrey, Alexandra. 2017. “Leaving Against Medical Advice (AMA): A Clinician’s Dilemma – In

Practice.” In Practice. May 11, 2017. https://blogs.jwatch.org/frontlines-clinical-medicine/2017/05/11/leaving-medical-advice-ama-clinicians-dilemma/.

Goodyear-Smith, Felicity, and Stephen Buetow. 2001. “Power Issues in the Doctor-Patient Relationship.”

Health Care Analysis 9 (4): 449–62. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1013812802937.

Jauhar, Sandeep. 2020. “Opinion | When Doctors Need to Lie (Published 2014).” The New York Times,

Johnson, Tyler. “The Importance of Physician-Patient Relationships Communication and Trust in Health

Care – Duke Personalized Health Care.” Duke Personalized Health Care, 11 Mar. 2019, dukepersonalizedhealth.org/2019/03/the-importance-of-physician-patient-relationships-communication-and-trust-in-health-care/.

Pearson, Steven D., and Lisa H. Raeke. 2000. “Patients’ Trust in Physicians: Many Theories, Few

Measures, and Little Data.” Journal of General Internal Medicine 15 (7): 509–13. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.11002.x.

Rankin, Elizabeth. 2019. “The Process of Shared Decision-Making: What It Is, When It’s Not, and What

It Should Be | – SPM Blog.” Blog: Society for Participatory Medicine. March 27, 2019. https://participatorymedicine.org/epatients/2019/03/the-process-of-shared-decision-making-what-it-is-when-its-not-and-what-it-should-be.html.