Abstract

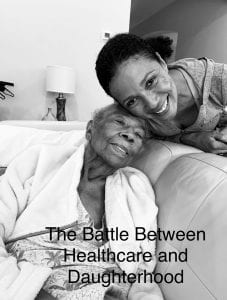

This is a personal narrative written from my mother’s perspective modeled after the lives of my mother and grandmother. It takes the audience through my grandmother’s journey with cancer which she was diagnosed with in July 2020 and took her life on December 8th, 2020. However, the story of their journey is a multi-dimensional one introducing various facets of the struggles of caring for a sick family member in the midst of a global pandemic. My mother is my inspiration for this piece because of the grace she exhibited during this period despite the internal struggles that she was facing. In addition to being my grandmother’s primary caretaker, she is also a healthcare provider herself at Houston Methodist Hospital. In this piece I share the relationship between her playing a large part in the hospital’s COVID-19 protocols and management while dealing with similar protocols from the opposing side as she cared for my grandmother. Additionally, because of her healthcare background I share some of her struggles when dealing with my grandmother’s healthcare experience such lack of patient advocacy, COVID-19 visitor protocols, and physician empathy.

Because of the strict protocols due to COVID-19 my mother was forced to instill a great amount of trust in my grandmother’s physicians which was a difficult task. Some of the sources that I used to support and further understand patient-physician relationships were sources about physician empathy, the relationship between healthcare staff and patient satisfaction, and patient-physician relationships. Additionally, I used sources about the current hospital protocols and why they are in place. Lastly, Ricardo Nuila’s “I Am a Rock” and Arthur Kleinman’s “Caregiving: The Odyssey of Becoming More Human” were very inspiring pieces for me to read. They both provided stories of family members and sick patients which was helpful for my writing.

To create this piece I did a series of “casual interviews” where I spoke to my mother and grandmother about their healthcare experiences. However, much of the piece I wrote from observation being that I was present for my grandmother’s journey and helped my mother with caretaking and support. The piece begins with an introduction and then goes into a series of chapters, each one telling a brief story that is significant to my mother’s journey.

Introduction

My mother never complains about anything. She won’t tell you if she isn’t feeling well or if she is unhappy. She just keeps pushing forward. She moved to Inglewood, CA with my father in the 1950s where she began her work as a cytotechnologist and he worked various small jobs. We didn’t have a lot of money, however my mother shielded us from this reality.

Growing up I always admired my mother’s work ethic. She worked as a cytotechnologist for 35 years in Los Angeles, and sent my sister and I to Catholic School. I believe her work ethic was present because she grew up in Mississippi in the 1940s. There weren’t many opportunities for Black people and she was forced to make her way out of the South in order to create opportunities for herself.

My mother was determined to send my sister and I to college. I attended University of California Berkeley and went on to attend University of California San Francisco for nursing school. I am not sure why I wanted to enter the medical field. However, I think it is because my mother’s caring and hardworking spirit was an inspiration for me to help others.

Soon after my father died my mother had a stroke. As she walked to work she fell against a parked bus on the side of the road and was rushed to the hospital. Her vision was blurry and she was never able to fully gain it back. She was 63 at the time. Due to my medical expertise she moved into my home in Atlanta, GA where we cared for her.

In Atlanta, GA I worked at Emory Healthcare Hospital as a Nurse Practitioner. I was able to care for my mother and keep track of her health. She was very healthy after this stroke and actually began to care for my children when my husband and I were away. She was a source of guidance and even though I was an adult, in a way she cared for me too.

However, 20 years later we moved to Houston, TX where my journey with work and my journey with my mother began to transform.

The Pandemic

“Have you been in close contact with anyone diagnosed with COVID-19 in the past 14 days? Have you had a cough? Runny nose? Fever? Chills? Sore Throat? Loss of –”, the front desk personnel recites. “No, I have not,” I respond abruptly.

Entering the hospital was like entering the airport. Instead of being shielded by harmful weaponry we were being shielded from a horrible disease that we still knew little about.

However, I am thankful for the protection. I walk through the halls that were previously loud and chaotic, but that now just have a gentle, peaceful humming in the background. The halls that previously had families of 10 walking through with bouquets of flowers now had individual mourning family members walking alone. I am thankful for it.

As I arrive at my office, I see a paper on my desk. “CoronaVirus Houston Methodist April” is written along the top of the sheet. I read the number “15” and sigh knowing that it is going to be a long week ahead of me. Though 15 seems like a small number, this represents 15 healthcare providers. 15 individuals contracting COVID-19 from people within our hospital doors. Hospitals should be a safe place.

Away from the Chaos

I’m burned out. I go to work early and come home as the sun goes down. I spend the day fighting a virus that seems to be stronger than the healthcare providers fighting against it. I dream of a life in which coronavirus does not exist. I dream of a life in which I am not a healthcare provider. But instead of giving into these daunting dreams, I simply take a break.

Martha’s Vineyard, an island off the coast of Massachusetts is the most isolated and remote location I could find to remove myself from the chaos of coronavirus. I still have to work, but at least I can do so under the stars, unmasked and safe rather than in my office with the constant reminder of the state of the hospital. My mother has a doctor’s appointment this week, however my sister has come into town, releasing the burden off of me.

We eat hot dogs and chips under the setting sun. I watch as my kids lounge in the pool beside one another. I read a book. And for a second I forget about the realities of the world. I forget that my mother has a check up today. All of my stress about her health gently exits my mind. I forget that the virus’s cases are rising, particularly at Houston Methodist. I feel a glimpse of happiness and joy. However, in what feels like seconds the ringtone of my sister blares through the air. I ponder whether I should answer the phone to disrupt my serenity, but give in remembering that our mother had an appointment an hour prior.

“Hey, I have the doctor on the phone for you,” she claims.

Before even listening to the doctor’s voice every possible source of bad news flashes through my mind like a slideshow. I am so heavily consumed with my thoughts that I barely listen as the doctor begins to discuss my mother’s health through the phone. I quickly snap back in to listen.

“Her blood sugar is low and we did find that she has an infection,” the doctor gently explains. I take a deep breath in. “And there is some reason to believe that we may need to do more scans,” he further claims. I heavily exhale.

Life Ends Eventually

Waiting for my mother’s scans to come back is like waiting for a wave to hit you in the ocean. Either it’ll be underwhelming and gently float to shore or it’ll take you out. The only reality that I could process was the latter in which I found out horrible news.

I sit in the same lounge chair and watch as my kids lounge in the pool listening to music, but this time all I can think of is home. My body is on vacation, but my mind is not.

My mind remains on these thoughts even as we leave. My husband is driving the car, tapping the steering wheel to the beat of “When Doves Cry” when the phone rings. This time a woman is on the other end of the line. She has a cheery voice. It is kind, but not empathetic. It does not have the correct mixture of kindness and sympathy as a doctor’s voice should. Before I could even mutter a “hello” she says, “We think we found a mass on your mother’s liver that we believe might be a result of pancreatic cancer but –.”

“Sorry, please slow down,” I mutter. “Yeah, we won’t know until the oncology specialist comes in though,” she follows up. I say nothing. I don’t know what to say. In the background I hear the voice of my mother however. She says, “Well, I am going to die somehow.” The laughter of the physician echoes through the speaker.

She seems to find that funny. I do not.

A Terminal Illness

My mother has a terminal illness. She is deteriorating quickly. I now have two jobs. I must care for my mother and in a way care for the world as I play a part as a healthcare provider in a pandemic.

At home I step behind my mother and gently lift her beneath her arms. “You’re going to drop me!” she exclaims frantically. However, my grip is firm and stable. I hold her as she rubs her hands together and washes them beneath the faucet. I hand her a cloth and she gently shovels her hands through the fabric. I roll her back to the couch and lay her head against the pillow. I watch her as her eyes slowly close and she falls into a deep sleep. I watch her throughout the day as she falls into and out of deep sleeps. I bring her small rations of food and she nibbles off the plate.

At night I lay awake waiting for the ringing of the “baby cam” signaling me to help my mother to the restroom. I feel as if I am never in a deep sleep. However, this is an alternative that I prefer than my mother not being at home.

Through the Eyes of a Visitor

“Have you been in close contact with anyone diagnosed with COVID-19 in the past 14 days? Have you had a cough? Runny nose? Fever? Chills? Sore Throat? Loss of –”, the front desk personnel recites. I cut in and respond in my usual manner and begin to walk through the halls of the hospital.

However, now the individual mourning family members walking alone don’t spark a feeling of safety, but sadness. I watch as they are told to leave the hospital because it is past “COVID visiting hours”. I see the distress on their faces. One particular patient cries belting out that her mother is all alone. Her mask is rapidly soaked with tears like a towel and she is told to leave the hospital.

Previously, these actions didn’t phase me. They didn’t really make me feel sad, but now I place myself in their shoes. I am a healthcare provider and the daughter of a terminally ill patient.

No Visitors Allowed

I walk downstairs into my mother’s room where she lies in bed, her eyes struggling to remain open.

“Good morning mommy!” I exclaim.

The energy is typically matched, but this morning there is a dullness in her voice. I lift beneath her arms but this time am greeted with dead weight. There is a weakness in her strength and her voice. I place my hand upon her head and feel the heat radiating from her. I take her temperature and see 101. In an 85 year old person this is frightening. I rush her to MD Anderson where they immediately take her into their facility, but I am left behind.

I feel conflicted. I understand why I am kept out of the facility, so I keep my calm. But deep down I want to cry and scream and be with my mother. I hand her her cell phone and frantically scream, “Call me when you make it to the room!”. I wipe a tear that slowly trails down my face and leave the facility.

Little did I know I would not see my mother for a week. During COVID-19 the protocol for MD Anderson is a “no visitors policy”.

I sit at home anxiously waiting for my phone to ring. I watch the clock as hours pass without any information on how my mother is doing. She is 85. She needs an advocate.

I am used to asking the physician numerous questions when they come in to see my mother. My experience in the healthcare field has taught me to ask as many questions as possible or they will take shortcuts. Maybe this is a reflection of myself. I am frantic realizing the fact that my mother’s advocate is now non-existent.

I am a healthcare professional. I understand the power of burnout. I know how this powerful force can reduce empathy. I understand the tendency to take shortcuts. This makes me all more afraid for my mother’s fate.

She is old. She is kind. She will not question your medical care. But I will.

Phone Call

I listen as the doctor gently sniffles through the speaker of the phone.

“Your mother is so gracious. She never complains and is so thankful for her life”.

“It is helpful when people aren’t overly emotional,” he says.

I feel proud that my mother is who she is. However, the oncologist’s words strike me as insensitive. My mother is 85 years old and has been awarded the luxury of a long life. Some of his patients aren’t awarded that luxury.

Maybe the Last Visit

I kiss my mother on the cheek, and say, “I love you and I will see you soon.” She opens her mouth to respond when suddenly she freezes. Her eyes roll back and she begins to shake violently in the hospital bed.

“You have to leave now,” the nurse in the room exclaims. I am ushered out of the facility all in one single moment. I feel like I am living in a nightmare. I cross the street to Houston Methodist and enter my office where I have a stack of papers about the vaccine protocols.

I want nothing more than to just be with my mother. In front of me sits a stack of papers that seek to help millions of Americans. They keep me out of the hospital where my mother lay to prevent these healthcare providers from catching COVID.

But there has to be a balance. For a child. For an elderly woman. Being alone isn’t adequate.

Goodbye

I sit by her bed, her fingertips cold and blue. Her breaths are slow and raspy. I watch her chest as she inhales and exhales. “Do you hear me mommy,” I speak softly into her ear.

She does not respond, but I know she is there. I watch her as her breaths slow and come to a halt. I place my hands along her eyelids and shut them. I lean over and whisper in her ear “I love you mommy.”

Just days before she was able to speak and to squeeze my hand. Today she is gone. It makes you wonder what happens in the days in between. I had two battles, COVID-19 and Cancer. I started my life caring for my mother and she ended her life with me caring for her.

References

CDC. 2020. “Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19).” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. February 11, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/non-us-settings/hcf-visitors.html.

HOCKENBERRY, JASON M., and EDMUND R. BECKER. “HOW DO HOSPITAL NURSE STAFFING STRATEGIES AFFECT PATIENT SATISFACTION?” ILR Review 69, no. 4 (2016): 890-910. Accessed November 14, 2020. doi:10.2307/26726516.

Farin, Erik, and Michaela Nagl. “The Patient-physician Relationship in Patients with Breast Cancer: Influence on Changes in Quality of Life after Rehabilitation.” Quality of Life Research 22, no. 2 (2013): 283-94. Accessed November 14, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24722702.

Kleinman, Arthur. 2009. “Caregiving: The Odyssey of Becoming More Human.” The Lancet 373 (9660): 292–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60087-8.

Nuila, Ricardo. (2016) 2020. I Am A Rock.

Smajdor, Anna, Andrea Stöckl, and Charlotte Salter. “The Limits of Empathy: Problems in Medical Education and Practice.” Journal of Medical Ethics 37, no. 6 (2011): 380-83. Accessed November 14, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23034748.