Monsanto Poisoned Us: The open secret of how America’s industrial monopoly is killing us

Abstract

For over four decades, a small town of around 30,000 people in eastern Alabama was unaware that they were actively being poisoned by a toxin called polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). From 1929 to 1971, Monsanto Industrial Chemicals Co. dumped 250 pounds of PCBs into Snow Creek – the heart of Anniston’s Black residential community – everyday decimating Anniston, Alabama’s population . Nearly 20 years after a class action lawsuit and a $700 million settlement, residents of Anniston are left to cope with the damage left after the production of PCBs were stopped in 1971. Polychlorinated biphenyl is a “dioxin-like” compound that was commonly used as coolants, in microscope immersion oils, carbonless copy paper, and pesticides. Notably, this compound is fat-soluble and biomagnifies as one goes up in the food chain. In areas where production of PCBs occurred, the toxin can accumulate our food supply and is found in fish, dairy, and poultry. When ingested, the PCBs can affect the body’s ability to fight infection, increase rates of autoimmunity, lead to cognitive and behavioral problems, type 2 diabetes, cancers, and hypothyroidism. In this piece of journalism, I aim to reconcile my experiences growing up with a myriad of health issues in my family and unusual amount of funeral attendance with my family’s toxic hometown. Through sources such as the Environmental Protection Agency’s archive and past news articles, I will also examine how and why Monsanto was able to get away with poisoning the town’s residents for so long. This act of environmental racism has left my family to deal with diseases like endometriosis, lung cancer, and diabetes and relatives lost early while many others deny that PCB has any chronic effects.

Content

I inherited my brown eyes and asthma from my dad. My wide smile and severe allergies from my mother. Growing up, I was a sickly child having begun taking weekly allergy shots at two years old and my first surgery to remove my infected tonsils at three. Even today, I still have a yearly visit to the ER when my lungs begin to feel like deflated paper bags once the temperature drops in winter. During the pandemic, my family and I have become hyper-vigilant about washing our hands and staying at home (we were all homebodies anyway).

Early on in the COVID-19 pandemic, it was discovered the Blacks and Hispanics were more severely affected by the virus than other races in America. According to the Center for Disease Control, Hispanic and Black Americans were 4.1x and 3.7x more likely to be hospitalized due to the virus than White Americans, respectively. Both races are 2.8x more likely to die from the virus than Caucasians. This did not come as a surprise to many as these racial groups are known to be more prone to chronic disease such as diabetes and high blood pressure.

The disproportionate connection between chronic disease and minorities has been widely accepted in medical literature, such to the point that correction factors when measuring the kidney function of African Americans. Yet, when probed to answer why Blacks and Hispanics have such ill health, the responses were highly varied with some being problematic. A recent example of such a response was the US Surgeon General’s plea in April for Blacks to stop drinking and smoking to “[d]o it for Big Mama” and avoid the use of tobacco and alcohol to aid in the slowing of the virus spread. Additionally, the diets of the two minority groups are also frequently blamed for the high rates of disease since they are high in fat and cholesterol.

However, Blacks and Latinos are nuanced people, just like every other race. Not every Black person smokes cigarettes and not every Latino eats fatty foods. Coming from a Black American family that has a generally healthy lifestyle and is still overrun with chronic conditions, these attributions to our health practices and diet don’t cut it.

On May 22nd, VOX released a video exploring how the environmental factors of where Americans live could explain the racial disparities seen with COVID-19. This caused me to explore my own family’s history in a small town in Alabama, the Monsanto Chemical Company, and how it may be connected to our current ill health.

Part One: The Invasion

As the nation was still reeling from the effects of the Great Depression, Rayfield Horton, my great-grandfather, took up a new position as a janitor at the Swann Chemical Company’s manufacturing plant in Anniston, AL. Anniston was a small town in the northern area of the state – home to around twenty thousand people. The town had seen a boom in the population after the establishment of Fort McClellan in 1917 as a military training camp.

African Americans in Anniston were mainly descended from slaves and sharecroppers who began to transition into working the town’s major exports of iron, steel pipe, and chemical products. Since this was the Jim Crow South, the town was segregated with Blacks residing on the rural westside in housing projects and shotgun houses. Rayfield and his wife Pearlie Mae lived in a three bedroom shotgun house with five of their ten children: Willie, Mary, Annie, Glenda, and Ralph.

The Hortons were a blended family: eight of the children came from Pealie Mae’s previous relationships. Three of her children remained in Rome, Georgia where the family migrated from after the Cotton Bust of the Great Depression. Her other son, Bill, ran away to work with a travelling circus. Rayfield was a fixture in his community because of his involvement in Murray’s Temple Church as a usher and leading Wednesday night Bible study. Neighbors would describe “Mr. Rayfield” as a friendly man who kept to himself, who could be seen spending time with his family on the porch as he chewed tobacco.

From before sunrise until supper, Rayfield toiled away at his job to support his family of seven in Anniston. “My grandfather would come home and he would take off his boots and uniform. [Then] my father and his siblings would play and stomp around in his boots,” Stephanie, my mother, reminisced. Everyday for the next 35 years, Rayfield worked maintaining the equipment and cleaning the floors at the chemical manufacturing plant until his retirement in 1969.

In 1935, the Monsanto Chemical Company purchased the Swann Chemical Co. to produce polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), marketed as Aroclor®. Polychlorinated biphenyls were a highly profitable good as the chemicals were virtually indestructible since they were designed to be resistant to heat, water, and chemicals. As a result of the New Deal’s Rural Electrification Act and that industrialization brought on by World War II, PCBs took America by storm. PCBs were used in electrical insulation, flameproofing, temperature control equipment, adhesives, and even chewing gum.

Soon after Monsanto acquired the plant in Anniston, there was already growing research in the harmful effects of chlorinated compounds. In 1937, the Harvard School of Public Health hosted Cecil Drinker at a conference to discuss clinical cases of liver damage, skin irritation, and infections in men who worked with compounds similar to PCBs.

Drinker wrote a report to the Monsanto Chemical Company and concluded that the chlorinated biphenyl compounds were “so definitely toxic” and emphasized that it was “imperative that whenever [the] compound is used in industry, great care [should] be taken to keep concentrations in the air at a very low level. As a result of these findings, in 1944, the Monsanto Chemical Company provided warnings to their salesmen about the hazards of Aroclor but failed to provide the same warnings and protective gear to their African American employees that made up most of their maintenance staff.

Part Two: The Assault

A few years after his retirement, my mother, Stephanie, began her schooling at Johnston Elementary on the east side of Anniston. Schools in the city had just integrated in the decade before. Despite its location in Anniston, Johnston Elementary’s student population was predominantly African American as many of the white students transferred to private schools or moved out of the city altogether. The school was privileged by Alabama standards and boasted a computer lab, enough textbooks for every student, and even a gymnasium where the yearly snake presentation was held. However, the segregated water fountains remained – a haunting reminder of the very recent Jim Crow past.

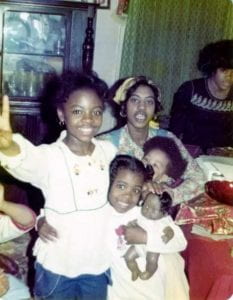

Born after the Brown vs. Board of Education ruling, Stephanie knew no difference and made friends with students of all races. Most of her friends were neighbors in the housing project she resided in. Like many children pre-digital age, Stephanie and the other project kids would spend hours outdoors playing in the water in the ditches and making mud pies. By the time she was eight years old, Stephanie’s parents divorced and her mother moved the family from the two bedroom apartment in the projects to a three-bedroom home a few blocks away. Now a single mother, Nanny, my grandmother, worked full-time at a local department store to put food on the table for my mother and her siblings. Although she didn’t have much, my mother was more than satisfied with what she had. Even today she boasts, “We grew up in the projects, but my mother always made sure we had name-brand food.”

As Stephanie grew older, her grandparents began to experience some issues with their health. By the mid-70s, all three of her grandparents suffered multiple strokes while only in their late forties and early fifties. Pearlie Mae began to notice black discharge coming from her breasts and was diagnosed with late stage breast cancer. During the time, breast cancer was seen as a taboo subject and many Blacks were unaware of the cancer’s signs and symptoms. Additionally, my mother’s family only went to the doctor if severely ill, so rarely did her family ever have any physicals. Pearlie Mae’s cancer had progressed too far by the time she was diagnosed and decided against receiving treatment. Pearlie Mae succumbed to the cancer only a few years after her diagnosis in 1979.

By 1969, Monsanto was Anniston’s largest employer and had been dumping 250 pounds of waste into Snow Creek – West Anniston’s water source – for almost thirty-five years. In response to European scientists’ claims that polychlorinated biphenyls were toxic, Monsanto ran multiple internal studies on the chemicals throughout the late 60s and 70s. In 1966, Monsanto recruited Professor Denzel Ferguson from Mississippi State University to investigate possible health effects resulting from exposure to PCBs. Mississippi State’s biologists released bluegill fish into Snow Creek . All twenty-five died less than four seconds later. When the findings were reported to the company, Monsanto buried the data and filed the reports as confidential. In a follow up study using rodent models, researchers then discovered that subjection to PCBs resulted in tumor formation. Yet, in a similar response to the 1966 findings, Monsanto manipulated the study’s conclusions to be changed from PCBs being “slightly tumorigenic” to “does not appear to be carcinogenic”. Despite the biologists’ damning findings, Monsanto never reported them or warned the town’s residents.

However, due to growing knowledge in the scientific community of the dangerous effects PCBs could have on the human body, Monsanto was pressured to quit production of Aroclor in 1977. Two years later, the EPA ordered a nation-wide ban on the production and use of polychlorinated biphenyls officially ending Monsanto’s monopoly of the lucrative chemical product.

Part Three: The Battle Won

On a January day, my mother received a call from her childhood best friend. “Did you hear the news about Monsanto? You need to watch this now.”

The Community Against Pollution was created by David Baker, a former union organizer and Anniston resident, to pressure chemical companies to clean up the contamination they were responsible for in the town and to compensate those harmed by it. By this time it was clear that something was wrong with the health of people in Anniston; most families in the town had at least one cancer diagnosis, developmental disorders, and neurological issues.

As a result of his efforts, the Environmental Protection Agency tested the soil, water, and residents’ blood for levels of PCBs. My own family was tested along with thousands of other members of the community.To the EPA’s horror, Anniston’s residents had the highest recorded levels of PCBs in the nation.

“… we had played in the ditches, made mud pies, eaten fish from the creek, and had a garden over on 12th street. It was in the water which was in the soil that the vegetable grew. We were drinking water outside of water holes. We were very shocked to find out they had been dumping [PCBs],” my mother reflected.

Both of my parents, my aunt, and my older brother had higher than safe levels of polychlorinated biphenyls in their blood. Nanny also tested for high levels of PCBs in her blood. Two weeks after receiving her settlement check of $2,000, she was diagnosed with lung cancer.

“She would have been entitled to a larger amount. But because she cashed the check before her diagnosis, there was nothing that they could do,” my mother recalled.

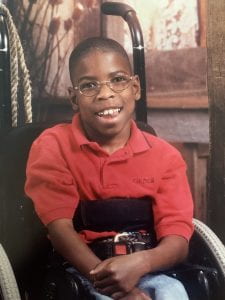

After receiving the test results, my mother and many of her old friends and neighbors began to connect the dots. During the 1990s, my mother’s generation began to experience severe health complications such as preterm labor, pre-eclampsia, and children born with congenital defects. My own brother was born at only twenty-five weeks in gestation in November 1991 and was diagnosed with cerebral palsy at one years old. Mere weeks after his birth, my mother’s friend also gave birth to a preterm baby with cerebral palsy. That same year, our family friend John lost both his twin infant daughters due to complications with being born prematurely.

In 2003, the resident’s of Anniston won a lawsuit against the Monsanto Chemical Company and Solutia Inc. (a divestiture of Monsanto). In the settlement, the two companies had to pay $700 million to more than 20,000 residents as a result of the PCB contamination to cover damages, court fees, clean up and research. This was a bittersweet victory for many as the checks were able to cover medical bills and support the cost of care but now residents must reckon with their permanently damaged health.

Part Four: The War Continues

In September of 2005, my extended family gathered together to celebrate what they all knew would be my grandmother’s last birthday. The cancer had metastasized to her brain. I was too young to know what cancer was, but I remember Nanny growing increasingly frail every time I saw her. The chemotherapy had taken away her auburn brown hair and her skin was paper thin and so dry that wrinkles appeared where they hadn’t before. On the weekends, Nanny used to sit me in her lap and read me Pippi Longstocking as she challenged me to spell and pronounce big words. As her illness progressed her voice became so weak that you could barely make out the words she spoke. We never finished Pippi Longstocking.

Nanny died three months later – nine days before Christmas and an hour before I could get to her house to say goodbye. Her funeral would be followed by twelve others in the family over the course of the next 15 years. While some were accidents or old age, many relatives died before reaching 60, including my grandmother. As I got older, I began to notice how my classmates would be shocked when I mentioned me going away over the weekend for a funeral. They had never been to one. Their grandparents got to live to their 80s while I lost both of mine by the time I started middle school.

My parents turned fifty this past October and have lost countless high school classmates to chronic disease and cancers. After losing one friend in the early 2000s, they have begun to lose count of how many of their friends are battling breast cancer. Those fortunate enough to not have a cancer diagnosis instead suffer from illnesses like diabetes, high blood pressure, lung disease, and autoimmune disorders.

In my own family, my mother, great-aunt, and sister suffer from rashes and joint pains caused by lupus. Auntie Angie can barely walk up the stairs without losing her breath due to severe asthma and five years have passed since she got off a ventilator after suffering complications with her kidneys. My dad has to take insulin daily and I hold my breath every time he leaves the house during the pandemic. Everyday, I struggle with feeling that there’s a timebomb ticking for every member of my family. I get lightheaded every time my mom calls me and has on her “bad news” voice. Monsanto did this to my family, but there are countless other families who have been victims to this environmental racism even today.

This past April marked six years since the Flint Water Crisis where thousands of people were exposed to dangerous levels of lead from the water pipes. Twelve deaths have been directly connected to the crisis and I am certain we will see many more. Over fifteen city officials were charged with crimes related to the crisis but every case against them has been dropped. Black Americans make up over fifty percent of Flint, Michigan’s population and I can’t help but to wonder if we would see the parties responsible behind bars if the town looked different.

In 2018, the Monsanto Chemical Co. was acquired by Bayer for $66 billion. In that same year, Bayer decided to discontinue the Monsanto name, erasing any chances for future accountability. In 2002, Robert Kaley, the former environmental affairs director told reporters that the company’s past actions should not be judged by modern standards. “Did we do some things we wouldn’t do today? Of course. But that’s a little piece of a big story,” he said. “If you put it all in context, I think we’ve got nothing to be ashamed of.” However, when actions of the past affect the lives of hundreds of thousands across America, who should be held accountable?

While it is easy to blame our consumption of fried foods and sweet tea, I think Americans and public health officials should consider how 400 years of systemic racism have also affected our health. From Tuskegee to Anniston to Flint, Black American bodies have been treated as expendable for the sake of scientific discovery and advancement of our society. The story of our struggle to build and belong in the nation is built in our DNA and literally flows through our blood. Rather than blaming the victims, more progress could be made if we started pointing our fingers at the institutions that made us this sick.

Works Cited

Anniston Environmental Health Research Consortium, et al. “Analysis of the Effects of Exposure to Polychlorinated Biphenyls and Chlorinated Pesticides on Serum Lipid Levels in Residents of Anniston, Alabama.” Environmental Health, vol. 12, no. 1, Dec. 2013, p. 108. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1186/1476-069X-12-108.

Chakraborty, Ranjani. “One Reason Why Coronavirus Is Hitting Black Americans the Hardest.” Vox, Vox, 22 May 2020, www.vox.com/videos/2020/5/22/21267365/coronavirus-black-americans-pollution-deaths.

Curtis, Sarah W., et al. “Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Differences and Polychlorinated Biphenyl (PCB) Exposure in a US Population.” Epigenetics, Taylor & Francis, July 2020, pp. 1–15, doi:10.1080/15592294.2020.1795605.

Espín-Pérez, Almudena, et al. “Identification of Sex-Specific Transcriptome Responses to Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs).” Scientific Reports, vol. 9, no. 1, Dec. 2019, p. 746. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1038/s41598-018-37449-y.

Harriet Washington. “Monsanto Poisoned This Alabama Town — And People Are Still Sick.” BuzzFeed News, 26 July 2019, https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/harrietwashington/monsanto-anniston-harriet-washington-environmental-racism.

Lauby-Secretan, Béatrice, et al. “Carcinogenicity of Polychlorinated Biphenyls and Polybrominated Biphenyls.” The Lancet Oncology, vol. 14, no. 4, Apr. 2013, pp. 287–88. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70104-9.

Markowitz, Gerald, and David Rosner. “Monsanto, PCBs, and the Creation of a ‘World-Wide Ecological Problem.’” Journal of Public Health Policy, vol. 39, no. 4, Nov. 2018, pp. 463–540. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1057/s41271-018-0146-8.

Michael Grunwald. “Monsanto Hid Decades Of Pollution.” Common Dreams, 01 Jan. 2002. https://www.commondreams.org/headlines02/0101-02.htm.

Pavuk, M., et al. “Predictors of Serum Polychlorinated Biphenyl Concentrations in Anniston Residents.” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 496, Oct. 2014, pp. 624–34. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.06.113.

The Associated Press. “$700 Million Settlement in Alabama PCB Lawsuit (Published 2003).” The New York Times, 21 Aug. 2003. NYTimes.com, https://www.nytimes.com/2003/08/21/business/700-million-settlement-in-alabama-pcb-lawsuit.html.

Silverstone, Allen E., et al. “Polychlorinated Biphenyl (PCB) Exposure and Diabetes: Results from the Anniston Community Health Survey.” Environmental Health Perspectives, vol. 120, no. 5, May 2012, pp. 727–32. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1289/ehp.1104247.

Yao, Mengyun, et al. “Polychlorinated Biphenyls and Its Potential Role in Endometriosis.” Environmental Pollution, vol. 229, Oct. 2017, pp. 837–45. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2017.06.088.

Yu, Mei-Lin, et al. “In Utero PCB/PCDF Exposure: Relation of Developmental Delay to Dysmorphology and Dose.” Neurotoxicology and Teratology, vol. 13, no. 2, Mar. 1991, pp. 195–202. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1016/0892-0362(91)90011-K.

Zahra Ahmad. “Flint Water Crisis Turns Six with No New Charges.” Mlive, 25 Apr. 2020, https://www.mlive.com/news/flint/2020/04/flint-water-crisis-turns-six-with-no-new-charges.html.