Pink Washed

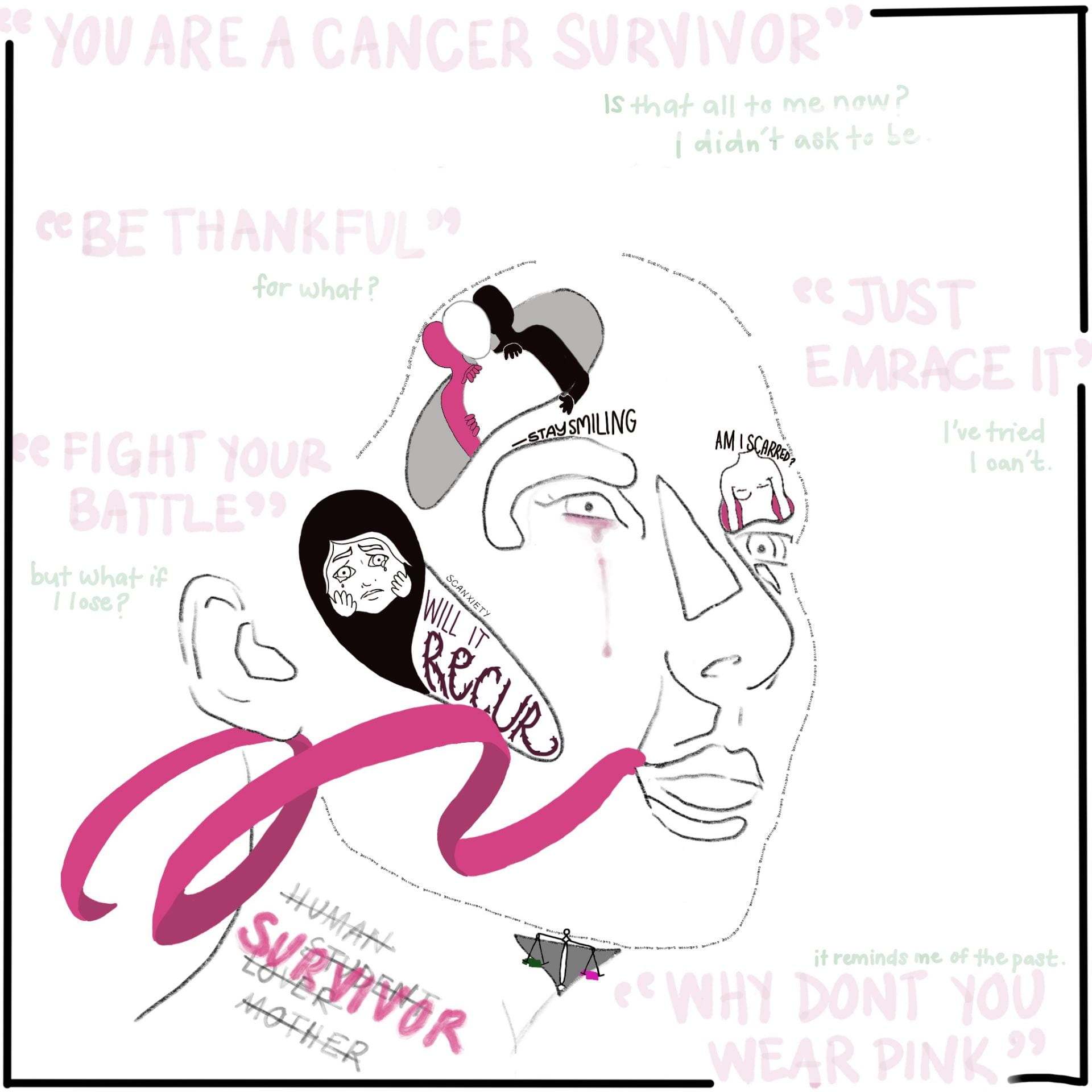

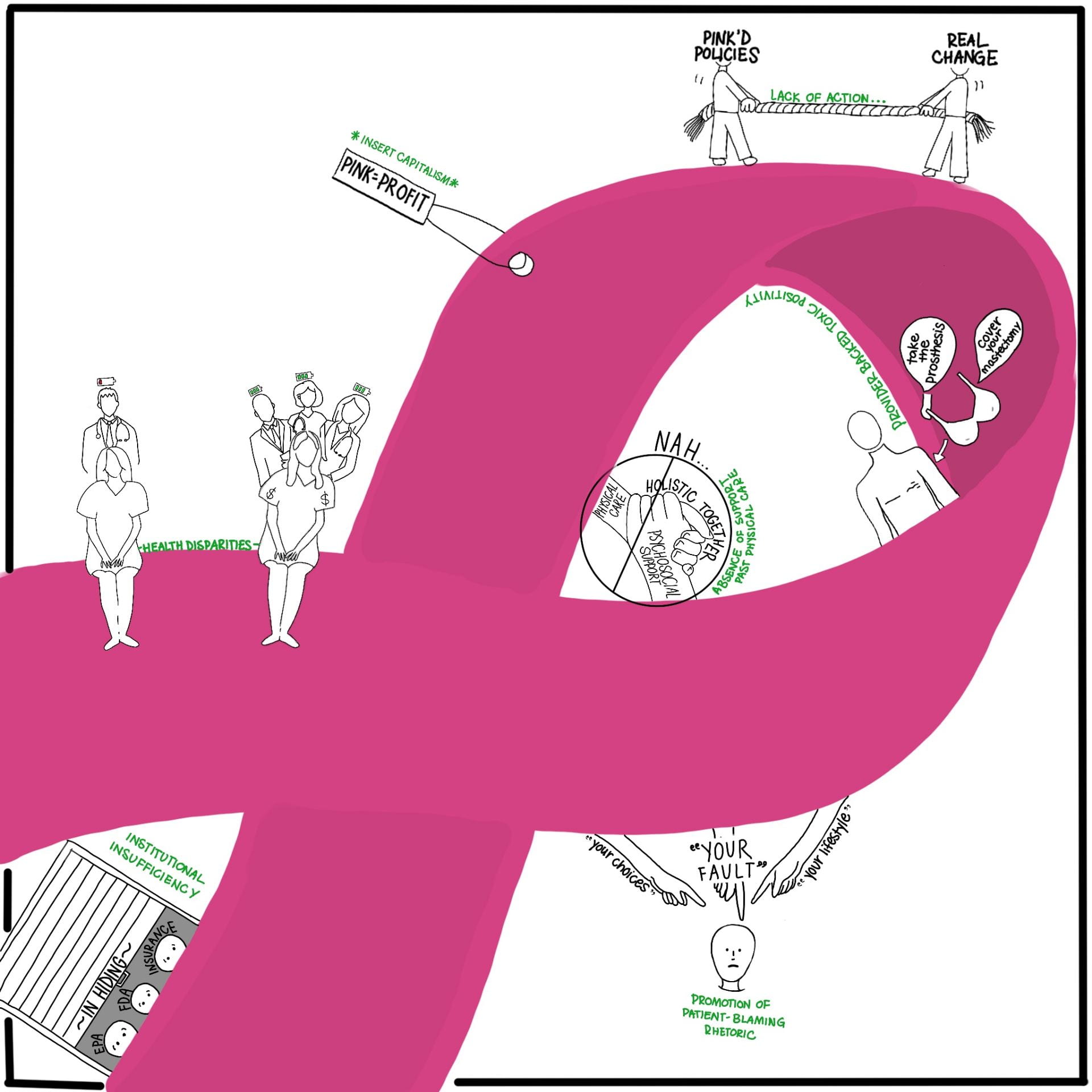

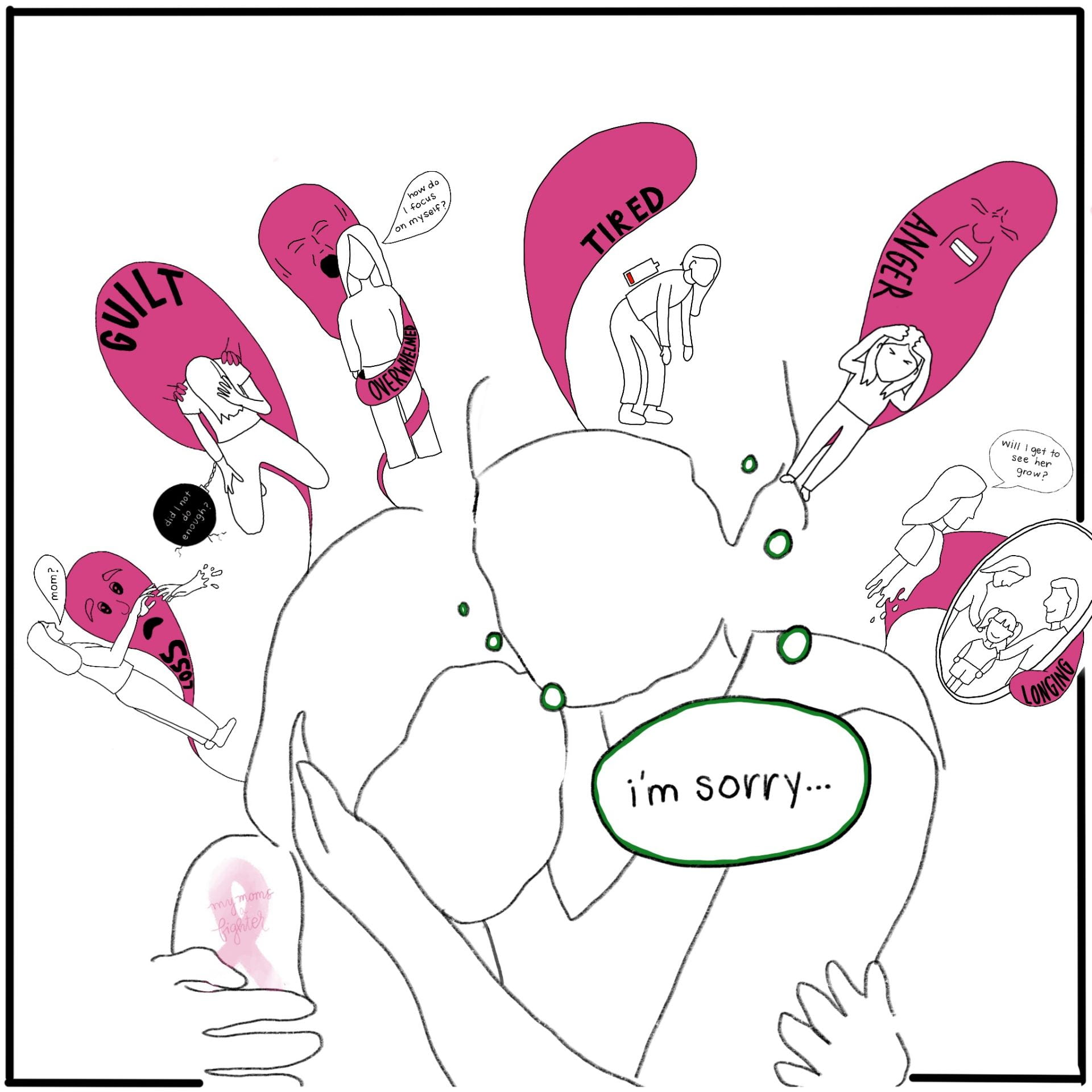

My mom, like many other individuals, had rung the cancer bells; she was told she was a survivor. She thought it was finally over. Then, less than a year later, she was diagnosed with recurrent breast cancer. Following my mom’s diagnosis and my experience as her caregiver, I was motivated to understand what it means to be a breast cancer survivor. To learn about the multidimensional nature of breast cancer, I broke up my research into three separate parts: the identity of a breast cancer patient and survivor, the roles healthcare providers and institutions play in working with patients, and finally, the bidirectional relationship between patients and co-survivors. Using published articles, excerpts from books, and online posts, I guided my research to strengthen my knowledge of the topic and better visualize the impacts of breast cancer survivorship through both facts and experiences. Each of the three parts have been divided into separate art pieces. I particularly picked art because it serves as an engaging form that easily captures an individual’s attention. The art consists of common breast cancer imagery/identifiers that will assist in building a representation of what breast cancer is and is not. The pink saturation of the three pieces is meant to serve as a widely-accepted introduction to breast cancer, but its excessive use will simultaneously highlight the problem of pink washing. While breast cancer is one of the most common cancers in the U.S, information regarding the disease is often washed pink. The real struggles of individuals are distorted by pink ribbons and marathons. And while the awareness garnered by these events is undeniable, the emotional consequences and subsequent lack of action cannot be ignored. I hope the audience will use these pieces to see breast cancer through a lens that moves past the typical understanding of the diagnosis and survival.

*Note: The experiences depicted in the artwork are not meant to be used as a generalizable characterization of the struggles of dealing with breast cancer. Rather, their purpose is to bring to light the plight of many individuals whose fight is often different from the standard portrayal of breast cancer.

The Individual: What does the post-cancer identity of being a survivor mean for women with breast cancer and how does it affect their socioemotional wellbeing?

The System: How do institutions both within the health care and outside of it limit access to quality care and support for breast cancer patients?

The Family: What is the emotional impact of breast cancer on bidirectional relationships between patients and their families (or caregivers)?

References:

Burke, Nancy J., Tessa M. Napoles, Priscilla J. Banks, Fern S. Orenstein, Judith A. Luce, and Galen Joseph. “Survivorship Care Plan Information Needs: Perspectives of Safety-Net Breast Cancer Patients.” Plos One 11, no. 12 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0168383.

Marshall, Catherine A., Terry A. Badger, Melissa A. Curran, Susan Silverberg Koerner, Linda K. Larkey, Karen L. Weihs, Lorena Verdugo, and Francisco A. R. García. “Un Abrazo Para La Familia: Providing Low-Income Hispanics with Education and Skills in Coping with Breast Cancer and Caregiving.” Psycho-Oncology 22, no. 2 (2011): 470–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.2108.

Nielsen, Emilia. “The Problem of Standardized Breast Cancer Narratives.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 191, no. 47 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.190549.

Rosenblatt, L. “Being the Monster: Women’s Narratives of Body and Self after Treatment for Breast Cancer.” Medical Humanities 32, no. 1 (2006): 53–56. https://doi.org/10.1136/jmh.2004.000212.

Smith, Tracy. October. “How Audre Lorde’s Experience of Breast Cancer Fortified Her Revolutionary Politics.” Literary Hub, October 11, 2020. https://lithub.com/how-audre-lordes-experience-of-breast-cancer-fortified-her-revolutionary-politics/.

Woźniak, Katarzyna, and Dariusz Iżycki. “Cancer: a Family at Risk.” Menopausal Review 4 (2014): 253–61. https://doi.org/10.5114/pm.2014.45002.